Walk This Way — or Maybe Not:

Breaking Down Fad Walking Trends

Walking is a terrific, almost universally accessible exercise. It’s one of the reasons that walking clubs, walking plans, and walking hacks are media staples. These days, social media is abuzz with three walking trends: Japanese interval walking, weighted-vest hikes, fart walking (yes, that’s the real term), as well as the ubiquitous daily step count. Let’s take a friendly stroll through the what, the why, and whether any of it really moves the health needle.

Japanese Interval Walking

What it is: A method that alternates 3 minutes of brisk walking with 2 minutes at a moderate pace, repeated over 30 minutes. As the name suggests, interval walking is a form of interval training, which involves alternating between bursts of intense activity and more gentle movement or rest. But compared with more classic forms of high-intensity interval training (HIIT), interval walking is more approachable for many people, especially those who haven’t exercised in a while or who are recovering from injuries that make high-impact activities like running difficult.

The science: The original study conducted in Japan (hence the name), and published in 2007, showed that interval walkers saw significantly greater improvements in blood pressure, cardiovascular health, and leg strength compared with volunteers who walked at a continuous, moderate pace. Since then, researchers have reinforced and even extended these findings. A 2018 longitudinal study found that, during a 10-year period, interval walking was linked to fewer age-related declines in aerobic capacity and muscle power.

Our verdict: Legit. You’ve got to love anything that slows down the aging process!

If you’re going to try it: The movement during the slow periods should be a gentle stroll. During fast periods, the idea is to feel as if you’re working somewhat hard, to the point that you would have a hard time carrying on a conversation. Over time, as your fitness improves, you will probably be able to push yourself harder during the fast bouts. In studies, the researchers capped the fast intervals at three minutes. If you haven’t been active in a while, start with a fast minute and work your way up.

The goal is at least 30 minutes of total walking per session. If you try it, those 30 minutes don’t have to be continuous. The research suggests that breaking the sessions into roughly 10-minute segments three times a day can be just as effective.

Weighted-Vest Walking

What it is: Throwing on a weighted vest (usually around 5–10% of your body weight) while you walk, to up the calorie burn and cardiovascular benefits. It’s like adding a little strength training to your walk. Exercising with a weighted vest is a variation on a military training exercise called “rucking,” where soldiers carry a weighted backpack (rucksack) on long treks and increase their weight loads over time. The difference between wearing a weighted vest and carrying a rucksack has to do with balance and core strength. A rucksack (different than your average backpack) requires the wearer to move with their shoulders, back, and core engaged. A weighted vest simply adds weight to your walk or other activities.

Many menopause and fitness influencers (some of whom make money on commission from selling the vests) pitch them as a way to add some resistance to walks, squats, and lunges, or even turn housework into a workout. Some claim the vests can help women in midlife maintain strong bones and muscles. One influencer recently went so far as to call weighted vests “one of the best-kept secrets” for healthy aging. Since the social media hype, several companies that sell weighted vests have seen a boost in sales, and last month, Peloton launched a series of weighted-vest walks. Weighted vests have become a fixture of the fitness world. It can be hard to walk in a park or on a hiking trail without seeing someone wearing one.

The science: A well-rounded strength-training routine is important especially for those looking to lose weight and for postmenopausal women: Starting in your 30s, you lose up to 8 percent of your muscle mass per decade, and more after you turn 60. Muscle burns more calories than fat does, so the more muscle you maintain, the more efficient your body is at maintaining or losing excess weight. Meanwhile, bone density plummets in the five to seven years after menopause, and half of women older than 50 will break a bone because of osteoporosis. A large body of research suggests that exercise can indeed help to strengthen your bones by strategically stressing them.

While exercise, especially strength training, is clearly beneficial to maintaining muscle mass and bone density, the jury is still out on the whole weighted vest idea. While wearing a weighted vest could theoretically strengthen bones by putting more force on them, the research on weighted vests and bone health isn’t as clear as we would like. Some small studies suggest that wearing a vest during resistance exercises may lead to modest improvements in muscle mass, strength, and bone health in some people. But even those studies don’t clearly reveal whether it’s the vest or the exercises that lead to those changes.

Most experts agree that wearing a weighted vest can modestly enhance your workouts by making them more challenging. If you like to walk or hike, a vest may offer greater aerobic conditioning by putting more load on your body, which forces your heart, lungs, and muscles to work harder — similar to walking on an incline or on a hilly path. And if you find that wearing a weighted vest motivates you to move more in general, the benefits could be even greater.

Our verdict: If you’re looking to burn more calories and increase your endurance, adding a weighted vest to your walk isn’t a bad idea, if you’re healthy and use proper form. But if you have back, knee, or shoulder issues, there are better, less risky ways to increase calorie burn and endurance. If you are looking to increase muscle mass and/or bone density, wearing a weighted vest during exercise seems better in theory than in fact. Strength training and resistance exercises will give you much better results. Wearing a weighted vest during exercise appears to have the greatest impact on two groups: deconditioned individuals seeking to increase calorie burn and improve strength with minimum intensity, and highly trained individuals looking for a performance advantage.

If you’re going to try it: If you choose to wear one, start with a vest that is five to ten percent of your body weight to avoid injury, or lighter, if you haven’t exercised in a while. Gradually add weight as you build strength. If you wear a vest while doing housework, be careful when bending or reaching to avoid losing your balance.

Please note: Wearing a weighted vest throughout the day does absolutely nothing if you don’t engage in significant activity. If you want a vest to make a difference, walk with it, do body weight exercises, or incorporate it into your training. Passive wear alone is not a thing.

Fart Walking (Post-Meal Jaunts)

What it is: Taking a moderate walk (typically 5–15 minutes) within an hour after eating. The name is cheekily literal, and surprisingly accurate.

The science: This habit helps trigger gut motility, which sends digestion into gear, eases bloating, aids blood sugar control, supports heart health, and can even improve mood. Mild-to-moderate exercise, such as walking, helps the stomach empty more quickly, improving transit through the intestinal tract and clearing out gas and waste through the digestive system, all of which can help alleviate issues like bloating and constipation. Walking promotes muscle contractions in the stomach and intestines that can lead to belching and farting. That quicker emptying will also decrease the time that acid is present in the stomach, which relieves heartburn in most people. This is one social media trend that science supports.

Our verdict: Not loving the name, but if you are looking to aid digestion, fart walking works. It’s simple and accessible to most of us. Just keep it short with moderate exertion and let nature do its thing. If you’re a bit shy, make it a solo activity

Revisiting the 10,000 Step Standard

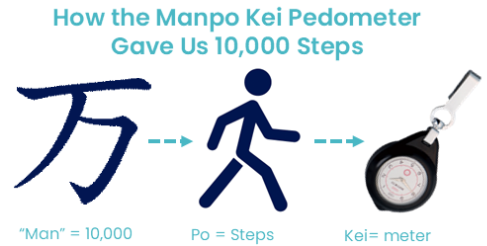

We all have the “10,000 steps a day” ideal burned into our brains. If the Japanese marketers who invented that notion are still around, they are probably very proud of themselves. The idea of walking 10,000 steps a day was invented as part of the marketing campaign for an early pedometer ahead of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. The Japanese character for 10,000 (“man”) looks (a little) like a person walking, so the device was called the Manpo-kei, which translates to 10,000 steps meter.

More than sixty years later, we’re still aiming for that completely arbitrary 10,000 steps. Before we all feel really silly, we should note that there is nothing terrible about trying to take 10,000 steps. It’s a noble, healthy goal. But we certainly shouldn’t feel like unfit failures for not getting there on a regular basis.

The good news is hundreds of studies have been done on walking during the past sixty years. We know that walking lowers mortality risk, reduces dementia risk, helps with weight loss, and contributes to living a longer, healthier life. As long as you don’t work your body into a state of exhaustion, more steps generally lead to better health outcomes. With that in mind, here are the latest consensus numbers based on the specific outcomes you are chasing.

To decrease your risk of dying from all causes: Taking just 2,500 steps a day can significantly reduce your risk. But taking more steps can increase the benefit. One study reported that people who took 8,000 steps daily were 50% less likely to die, compared to people who took 4,000 steps, during the nine years following the study. How quickly they walked had no impact on the findings. After a certain number of steps, the risk reduction does level off. Multiple studies suggest that the benefit plateaus at different step levels depending on your age:

- Adults 60 and older: Risk reduction increases until 6,000 to 8,000 steps.

- Adults younger than 60: The benefit plateaus after 8,000 to 10,000 steps.

To manage weight: The amount of weight you lose from walking depends on how much energy you use as you exercise. You either need to walk for longer or at a higher intensity for greater weight loss. But if you are looking for more specific guidance, researchers found that people who lose more than 10% of their body weight over 18 months walk approximately 10,000 steps a day. They walked at least 3,500 of those steps at moderate-to-vigorous intensity in short bursts (see Japanese interval walking).

To lower your risk of cardiovascular disease: To see a benefit, the sweet spot lies between 2,800 and 7,100 steps. Depending on how many steps you take, the benefit can be substantial. The American Heart Association reports that older adults who take 4,500 steps per day have a 77% lower risk of having an adverse cardiovascular event than people who take fewer than 2,000 steps. Each time you add 500 steps to your daily average, you incrementally lower your risk by 14%. However, the benefit plateaus between 6,000 and 8,000 steps.

To prevent dementia: Walking is good for your mind in many ways, and preserving your cognitive function is one of them. The more steps you take each day, the more your dementia risk declines. Once you hit 9,800 steps, the benefit plateaus. The good news is that you’ll begin seeing significant benefits at just 3,800 steps daily. Getting that many steps consistently may lower your dementia risk by 50% over time.

The Bottom Line on Walking

We agree that, within reason, more walking is better than little or no walking when it comes to health. If a viral walking trend inspires you, go for it. But when the trend fades, keep going, because when it comes to walking, consistency is key.

We’ve seen the following suggestions before, but they are worth repeating. Here are some non-trendy ideas to up your walking game:

- Take the stairs instead of using an elevator or escalator.

- Go for walks during lunch breaks, while meeting with friends, or while talking on the phone.

- Take regular breaks from working, watching TV, or reading to do something active.

- Add fun to your steps with dancing or hiking.

- Park further away than usual from stores or other destinations.

- Get off public transport a stop early and walk the rest of the way.